Read in our apps:

iOS

·Android

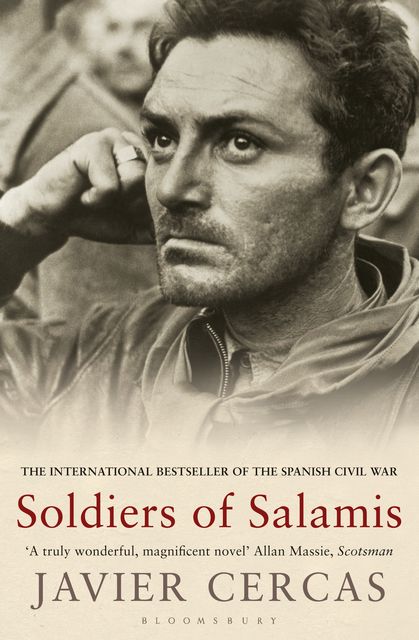

Soldiers of Salamis

- c13431682has quoted8 years ago‘It lays bare the virtual impossibility of historical certainty, the whimsicality of fate, the unpredictability and unreliability of memory and the elusiveness of truth … Cercas perfectly captures the uncanny ways in which a story evolves’

- c13431682has quoted8 years agoIf you were required to read only one book about Spain and its civil war, this should be that book.

- c13431682has quoted8 years agooldiers of Salamis is a study of memory and forgetting, of courage and delusion, as much as a straightforward narrative of wartime victors and victims.

- c13431682has quoted8 years agoAnd it rewrites the headlines of history on behalf of all of us who will be remembered – if at all–only in the smallest of small print’

- c13431682has quoted8 years agoMany of the people to whom I am indebted appear in the text with their full names; among those who do not, I want to mention Josep Clara, Jordi Gracia, Eliane and Jean-Marie Lavaud, José-Carlos Mainer, Josep Maria Nadal, Carlos Trías, and especially Mónica Carbajosa, whose doctoral thesis, The Prose of ‘27: Rafael Sànchez Mazas has been immensely useful. To all of them: thank you.

- c13431682has quoted8 years agoI saw my book, whole and real, my completed true tale, and knew that now I only had to write it, put it down on paper because it was in my head from start (’It was the summer of 1994, more than six years ago now, when I first heard about Rafael Sànchez Mazas facing the firing squad’) to finish, an ending where an old journalist, unsuccessful and happy, smokes and drinks whisky in the restaurant car of a night train that travels across the French countryside among people who are having dinner and are happy and waiters in black bow-ties, while he thinks of a washed-up man who had courage and instinctive virtue and so never erred or didn’t err in the one moment when it really mattered, he thinks of a man who was honest and brave and pure as pure and of the hypothetical book which will revive him when he’s dead, and then the journalist watches his sad, aged reflection in the window licked by the night until slowly the reflection dissolves and in the window appears an endless and burning desert and a lone soldier, carrying the flag of a country not his own, of a country that is all countries and only exists because that soldier raises its abolished flag; young, ragged, dusty and anonymous, infinitely tiny in that blazing sea of infinite sand, walking onwards beneath the black sun of the window, not really knowing where he’s going or who he’s going with or why he’s going, not really caring as long as it’s onwards, onwards, onwards, ever onwards.

- c13431682has quoted8 years agoAngelats and Maria Ferré, and also about my father and even Bolafio’s young Latin Americans, but above all about Sànchez Mazas and that squad of soldiers that at the eleventh hour has always saved civilization and in which he wasn’t worthy to serve but Miralles was, about those inconceivable moments when all of civilization depends on a single man, and about that man and about how civilization repays that man.

- c13431682has quoted8 years agothere I suddenly saw my book, the book I’d been after for years, I saw it there in its entirety, finished, from the first line to the last, there I knew that, although nowhere in any city of any fucking country would there ever be a street named after Miralles, if I told his story, Miralles would still be alive in some way and if I talked about them, his friends would still be alive too, the Garcia Segues brothers – Joan and Lela – and Miquel Cardos and Gabi Baldrich and Pipo Canal and el Gordo Odena and Santi Brugada and Jordi Gudayol would still be alive even though for many years they’d been dead, dead, dead, dead, I’d talk about Miralles and about all of them, not leaving a single one out, and of course about the Figueras brothers and

- c13431682has quoted8 years agowhen he opened the garden gate I felt a sort of premature nostalgia, as if, instead of seeing Miralles, I were already remembering him, perhaps because at that moment I thought I wasn’t going to see him again, that I was always going to remember him like this.

- c13431682has quoted8 years agoMiralles stepped off the kerb and came over to the taxi, leaning his big hand on the rolled-down window. I was sure I knew what the answer was going to be, because I didn’t think Miralles could deny me the truth. Almost pleading, I asked him: ‘It was you, wasn’t it?’

After an instant’s hesitation, Miralles smiled widely, affectionately, just showing his double row of worn-down teeth. His answer was:

‘No.’

fb2epub

Drag & drop your files

(not more than 5 at once)