We use cookies to improve the Bookmate website experience and our recommendations.

To learn more, please read our Cookie Policy.

To learn more, please read our Cookie Policy.

Accept All Cookies

Cookie Settings

Read in our apps:

iOS

·Android

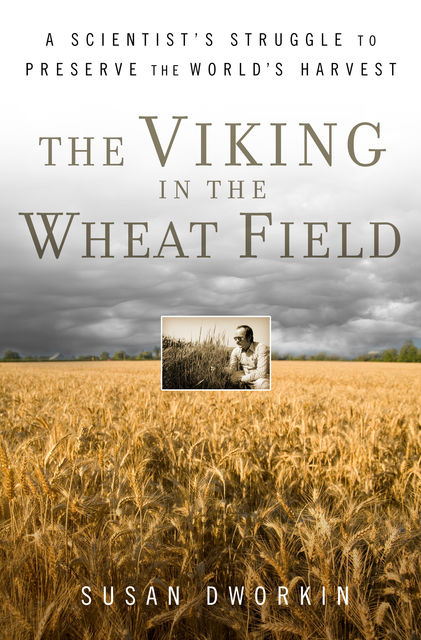

Susan Dworkin

The Viking in the Wheat Field

Notify me when the book’s added

Impression

Add to shelf

Already read

Report an error in the book

Share

Facebook

Twitter

Copy link

To read this book, upload an EPUB or FB2 file to Bookmate. How do I upload a book?

- About

- Readers2

In 1999, a terrifying new form of stem rust--spotted in Uganda and dubbed “UG99”--quickly turned robust golden fields into dark, tangled ruins. For decades plant scientists had bred wheat varieties with rust-resistant genes, but these genes did not work against UG99. Since rust migrates high in the atmosphere, it could spread from country to country, continent to continent. Breeders worried that UG99 would soon reach India and Pakistan, where 50 million small farmers produced 20% of the global wheat supply. If that happened, China, the world's largest wheat producer, might be next, and it would be only a matter of time before it reached American wheat fields. Breeders everywhere began searching wheat germplasm collections for sources of resistance. The largest collection was at the Center for Improvement of Maize and Wheat (CIMMYT) in Mexico, developed by the brilliant Danish scientist Bent Skovmand. For three decades, Skovmand amassed, multiplied, and documented thousands of wheat varieties. He served as an advisor on wheat genetic resources to dozens of countries, and hunted for seeds that would contain the genes to protect the harvest from plagues like UG99 and the stresses of global warming.From the mountains of Tibet to the jungles of Mexico, he trekked into fields to consult with farmers. In an era when corporations and governments often jealously guarded breeding information, Skovmand fought to keep his seed bank a center for free, open scientific exchange. By telling the story of Skovmand's work and that of his colleagues, The Viking in the Wheat Field sheds a welcome light on an agricultural sector--plant genetic resources--on which we are all crucially dependent.

more

This book is currently unavailable

273 printed pages

Have you already read it? How did you like it?

👍👎

fb2epub

Drag & drop your files

(not more than 5 at once)