We use cookies to improve the Bookmate website experience and our recommendations.

To learn more, please read our Cookie Policy.

To learn more, please read our Cookie Policy.

Accept All Cookies

Cookie Settings

Read in our apps:

iOS

·Android

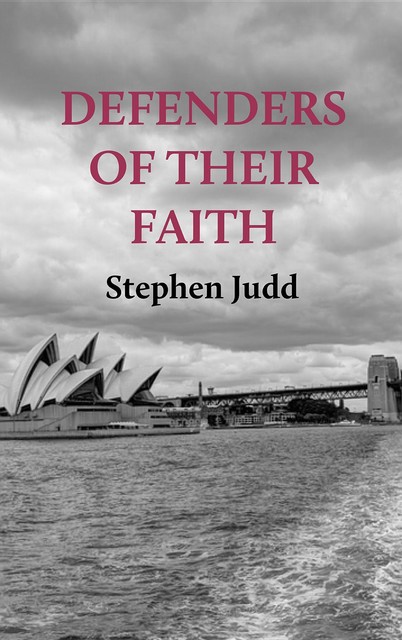

Stephen Judd

Defenders of their Faith

Notify me when the book’s added

Impression

Add to shelf

Already read

Report an error in the book

Share

Facebook

Twitter

Copy link

To read this book, upload an EPUB or FB2 file to Bookmate. How do I upload a book?

The diversity of opinions which were held by Anglicans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was, ideally, the ingredients of a unifying comprehensiveness. In fact, it was invariably the cause of unhappy and tense divisions, which gradually became institutionalised in respectable political organisations: the circumspection of churchmen towards “party” was replaced by a conviction that while factiousness was un-Christian, political societies were natural and, indeed, essential expressions of Anglicanism’s richness…

This study departs from this traditional model of diocesan history. Instead, it is contended that there lies within Anglicanism an inherent tension which has often produced a powerful political dynamic. The examination of that dynamic is far more crucial to an understanding of the polity than the study of the policies and actions of its bishops: in fact, this political dynamic was independent of the bishops, although that episcopal hierarchy was rarely independent of it. It is further contended that the importance of that dynamic was heightened in the ecclesiastical context of Australia. The potential for party conflict was limited in England by the constraints of Establishment. In Australia, however, the absence of Establishment, together with other historical and environmental factors, was responsible for the emergence of a self-determining Anglicanism in which mere lobbying for influence was metamorphosed into an outright struggle for power.

This dissertation is, therefore, a study of power and party in Anglicanism in Sydney, rather than the history of the Anglican Diocese of Sydney. It traces the political rather than the biographical or chronological. There is no close examination of parochial life or the relationship between church and society: these are areas which can be more successfully treated after the issues of ecclesiastical power have been clarified. At the same time, it must be insisted that the development of political structures, disputes over millinery and the phenomenon of struggles for power in the church’s decision-making councils are not divorced from the pew nor without social significance. No doubt the average parishioner and disinterested man in the street knew or cared little about these phenomena. But they nevertheless had a direct and profound bearing on the message which the pew and the society at large received. Social and economic conditions, ethnicity and other secondary factors did in part influence the form of that message and its reception, but it was the same sincere religious convictions which were at the heart of these disputes which were also the most formative and crucial factors in the developments and transmission of the message. Scholars who mistakenly attach pre-eminence to these secondary factors not only discount the importance and power of the sincerely-held beliefs of others but also project alien values onto their historical subjects. The primary impulse in ecclesiastical polities is transcendent not immanent, and when that impulse is expressed in political terms it is essential for those political phenomena to be the focus of the historical research rather than social, biographical or other issues.

This study departs from this traditional model of diocesan history. Instead, it is contended that there lies within Anglicanism an inherent tension which has often produced a powerful political dynamic. The examination of that dynamic is far more crucial to an understanding of the polity than the study of the policies and actions of its bishops: in fact, this political dynamic was independent of the bishops, although that episcopal hierarchy was rarely independent of it. It is further contended that the importance of that dynamic was heightened in the ecclesiastical context of Australia. The potential for party conflict was limited in England by the constraints of Establishment. In Australia, however, the absence of Establishment, together with other historical and environmental factors, was responsible for the emergence of a self-determining Anglicanism in which mere lobbying for influence was metamorphosed into an outright struggle for power.

This dissertation is, therefore, a study of power and party in Anglicanism in Sydney, rather than the history of the Anglican Diocese of Sydney. It traces the political rather than the biographical or chronological. There is no close examination of parochial life or the relationship between church and society: these are areas which can be more successfully treated after the issues of ecclesiastical power have been clarified. At the same time, it must be insisted that the development of political structures, disputes over millinery and the phenomenon of struggles for power in the church’s decision-making councils are not divorced from the pew nor without social significance. No doubt the average parishioner and disinterested man in the street knew or cared little about these phenomena. But they nevertheless had a direct and profound bearing on the message which the pew and the society at large received. Social and economic conditions, ethnicity and other secondary factors did in part influence the form of that message and its reception, but it was the same sincere religious convictions which were at the heart of these disputes which were also the most formative and crucial factors in the developments and transmission of the message. Scholars who mistakenly attach pre-eminence to these secondary factors not only discount the importance and power of the sincerely-held beliefs of others but also project alien values onto their historical subjects. The primary impulse in ecclesiastical polities is transcendent not immanent, and when that impulse is expressed in political terms it is essential for those political phenomena to be the focus of the historical research rather than social, biographical or other issues.

more

This book is currently unavailable

395 printed pages

- Original publication

- 2015

- Publication year

- 2015

Have you already read it? How did you like it?

👍👎

fb2epub

Drag & drop your files

(not more than 5 at once)